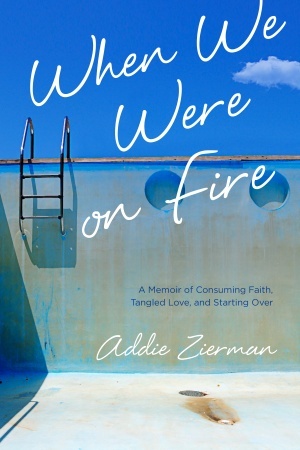

Today’s post is a combination link-up with Addie Zierman, whose memoir When We Were on Fire, releases today and a review of the book. (I received a free copy from the author in exchange for my review.) Check out the other posts in this synchroblog here.

“You can’t be a Christian unless you believe God created the world in six days!”

“Then I will NEVER be a Christian!”

Fifteen years later, I still cringe when I remember this exchange.

And it’s not just the words I said but the way I said them. I was so sure this was true. So convinced of its rightness. At the time, I thought I was acting out of love, attempting to passionately persuade the other person to see the truth.

But I think it was me who was blind.

—

I was home from college, a new Christian emerging from the protective cocoon of a campus fellowship group and learning to spread my wings in–but not of– the world. I was working for my hometown newspaper and had been assigned to cover an outreach event at a nearby church. The details are fuzzy to me now: why this event merited coverage at all. But there I was, sitting in a church gym reporting on a group of men who performed feats of strength while proclaiming the power of God.

The Power Team.

They ripped phone books in half. Bent bars with their teeth. And I don’t even remember what else. But I was caught up in the boldness and exuberance of it all, thinking this is what it must be like when God works mightily in your life.

It was the kind of outreach event that churches gravitated toward at the time: flashy and enticing. It would get people in the door to hear the message of good news, and once inside they would be unable to resist the altar call to give their lives to Jesus.

This was the event that preceded my all-or-nothing declaration. It was an argument, pure and simple. And though it didn’t have the intended result–conversion–I still felt I’d won.

Because I was learning what it was to be a Christian. And not just any Christian. An evangelical Christian. And by the very name, we were supposed to tell others about Jesus. And do it boldly and unashamedly because we wouldn’t want Christ to deny us if we’d denied him before men. So, that’s what I did. It didn’t matter that the person didn’t believe. It didn’t matter that I’d felt rejected and sad. Because I’d done my part. (Right?) I’d proclaimed the good news. (Hadn’t I?)

Now, I’m not so sure.

—

Fast forward 10 years. I’m a married woman with a baby living 800 miles from my hometown. My husband is in his first year of seminary at a school that has the word “evangelical” in the name.

He comes home one day after an Old Testament class and tells me this: his professor, a doctor who has studied the Old Testament his entire life, isn’t sure the world was literally created in six days.

My husband couldn’t have surprised me more if he’d told me the world was really flat.

I panicked and wondered if we’d made a mistake coming to seminary. (We hadn’t.) If it would ruin our faith. (In a way, it did.) If we would start to doubt everything. (At times, we have.)

Because he had a relationship with the professor, my husband was more easily convinced. I clung to what I’d been taught in my early days of Christianity, and we didn’t talk about it much.

—

In the middle of seminary, everything changed. We hit a crisis point in our marriage. We met faithful people with different theological beliefs from us. And we felt the “firm foundation” of our evangelical faith shift underneath us.

I don’t call myself anything anymore except a woman trying to follow Jesus. I don’t vote party lines but my conscience. I try not to argue points but listen to differing ideas. I still do it poorly.

But I’ve burned others and I’ve been burned, so when I think of being “on fire” now I picture a warm campfire and not a blazing forest fire.

—

I have felt guilty for the changes that have happened. But when I read a book like Zierman’s, I feel less so. Her “memoir of consuming faith” makes me feel a little more normal, and her faith journey’s timeline is similar to my own. There are parts of the book I feel like I could have written. It is funny, at times, and heartbreaking. I found myself nodding a little too vigorously and wanting to cry because our pains were similar.

I have felt guilty for the changes that have happened. But when I read a book like Zierman’s, I feel less so. Her “memoir of consuming faith” makes me feel a little more normal, and her faith journey’s timeline is similar to my own. There are parts of the book I feel like I could have written. It is funny, at times, and heartbreaking. I found myself nodding a little too vigorously and wanting to cry because our pains were similar.

I read it in two days, and I would read it again just to underline and make notes about the journey.

At points in the book, Zierman switches from first-person (I) to second-person (you), and though it’s unconventional it was absolutely essential to this story. Because it’s not just her story. It’s our story. And those second-person passages drew me in and helped me connect to my own part of the story. (My only caution is: if cursing bothers you, then don’t pick up the book. It’s not gratuitous but there are words that some might find offensive. I think Zierman was responsible in her use of them for the sake of authenticity.)

You can also read Zierman’s writing on her blog, How To Talk Evangelical.

And today, you can read others’ stories of triumph and tragedy within evangelicalism. Feel free to share your own, as well.