It is Wednesday and I am out for a run in the morning. I should be at work, but I am home instead keeping watch over my husband. He has appointments and I don’t want him to go alone. I don’t know if my staying home is more for me or for him. Regardless, I am home, and I am running because I need an outlet for all the feelings my body has been storing since Sunday.

As I cross an intersection where one road curves to the left and the other goes straight, nearing the stream, I look up and see this.

Is it a beehive? Is it a hornet’s nest? I don’t know for sure. All I know is I am struck by its beauty. I almost stop and take a picture but I am only a few minutes into my run so I keep going. But I can’t stop thinking about it. How it is beautiful and terrible all at the same time.

It reminds of me this quote (emphasis mine) by Frederick Buechner that is so often referenced when the world feels not as it should be.

“The grace of God means something like: “Here is your life. You might never have been, but you are, because the party wouldn’t have been complete without you. Here is the world. Beautiful and terrible things will happen. Don’t be afraid. I am with you. Nothing can ever separate us. It’s for you I created the universe. I love you.”

I think about this all throughout my run and when I have stopped running and begun my walk, I alter my route so I can go back and take a picture.

I want to remember that beauty and terror can co-exist.

—

On Sunday morning, we woke early as a family and gathered supplies, packing the car for a hike in the Poconos, two hours from home. We’d been wanting to hike this particular trail all summer but the weather wouldn’t cooperate. Every Wednesday, it seemed temperatures were too hot, humidity too high or thunderstorms were forecast. When the school year starts, our hiking intentions drop from weekly to monthly, and September is always scattered and stressful, so we were excited to finally be on our way.

Well, two of us were excited. The kids were whiny. They’re always whiny at the start of a hiking adventure, and they always get over it after an hour or less. True to form, before we even reached our destination, they were in better moods, and I was composing my after-hike Instagram post. Something like “Pro tip: pick a hiking destination more than an hour away so your kids get all their whining out of the way before you hit the woods.” It was going to be clever and make people chuckle. (It made me smile and that’s really the only reason I try to be funny: to amuse myself.)

It was just after 8:30 a.m. when we pulled into the parking lot, and the lot was filling up fast. We’d been warned of this, which is why we left so early. It took us 15 or 20 minutes to get our water packs and backpacks loaded up, to coat ourselves in bug spray. Then we were on the Appalachian Trail, hiking up the side of a mountain, on our way to Mount Minsi in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.

We walked past a lake and enjoyed views from various overlooks.

We crossed a creek and no one fell in. I stood on a rock in the middle of the creek and took a picture, just because I could.

We were having a glorious time. The weather was perfectly gorgeous. Nature does something healthy for my soul, and even though it wasn’t an easy hike, we were enjoying ourselves.

About an hour into the hike, we came to an overlook where the Delaware River was easily visible and across the river, we could see New Jersey.

We lingered, enjoying the view, taking pictures. And then Phil said he wasn’t feeling great. He was lightheaded, thinking he might pass out. He sat down. Drank some water. Nibbled a snack. The kids were getting a little restless and we asked them to find a way to calm themselves so Dad could keep calm.

After a few minutes, he thought he might try to keep going. Our path was winding away from the ridge and farther in and up the mountain. We went a little ways more and Phil had to stop again. There was a small clearing with a large rock, and he sat down. He felt lightheaded, nauseated, with a little bit of chest pain. At this point, I knew we wouldn’t be finishing our hike. We had 3.5 miles to go. But I was nervous about going back the way we came. If Phil couldn’t make it himself, there was no way the kids and I were going to be able to help him.

A few minutes passed and Phil said, “I think you better call.”

“911?” I said, just to confirm that’s what he meant.

“Yeah,” he said.

—

It’s around 10:30 a.m. on a Sunday morning and I am dialing “911,” something I’ve never had to do before. I will add it to a growing list of firsts in the coming days.

“911, where is your emergency?”

“We’re on the Appalachian Trail on the way to Mount Minsi.”

“And what’s going on there?”

I tell him about my husband’s symptoms. He takes my name and number, then the dispatcher and I try to work out where exactly we are. He asks if we’re in New Jersey, and I tell him we’re in Pennsylvania. He tracks my phone’s GPS. We’re talking and then my husband is talking to two hikers passing by.

“Hey, I’m having a little trouble. Are either of you medically trained?”

One of them says, “It’s your lucky day.” He’s an EMT, out for a hike. He doesn’t have any tools with him, but he talks to my husband, assessing his symptoms while I’m on the phone with the 911 dispatcher. He asks me to ask the hikers if they know our location. We decide we’re close to Lookout Rock. The dispatcher connects me with the National Park Service because we are in a national park. I forgot that when I was telling him our location.

They assure me that help will be on the way. Matthew, the EMT hiker, takes his leave after that. He has offered us a sliver of hope that this is not anything serious.

I text our parents, tell them we’re out hiking, that Phil is feeling weird and that we’ve called 911. I text one of the pastors at our church. It is 10:45 and the second service has just started. Everyone replies with words of encouragement, promises to pray. The kids sit down on a rock in the middle of the Appalachian Trail. I encourage them to eat. They move every time hikers pass us by.

“Hi. How are you?” everyone asks as they pass. We look like we’re just taking a break, have stopped for lunch. We don’t know how to tell them we’re waiting for rescue.

An officer with the NPS calls me. “We’re assembling a team,” she says. She tries to get more information about our location. When I hang up, I hold on to the hope that help is on the way.

Time passes. We all pee in the woods. We eat a little. Drink water. Phil doesn’t feel any worse but he doesn’t feel any better. He starts to have chills because he’s leaning against a rock, sitting on damp ground, and the sun hasn’t crested the mountain yet. I sit next to him, try to warm him with my body. I rub his back, his shoulders, trying to soothe him, all the time wondering who will soothe me when this is all over. Phil is the steady one, although even as I write that I know that we often take turns steadying each other.

The officer texts me.

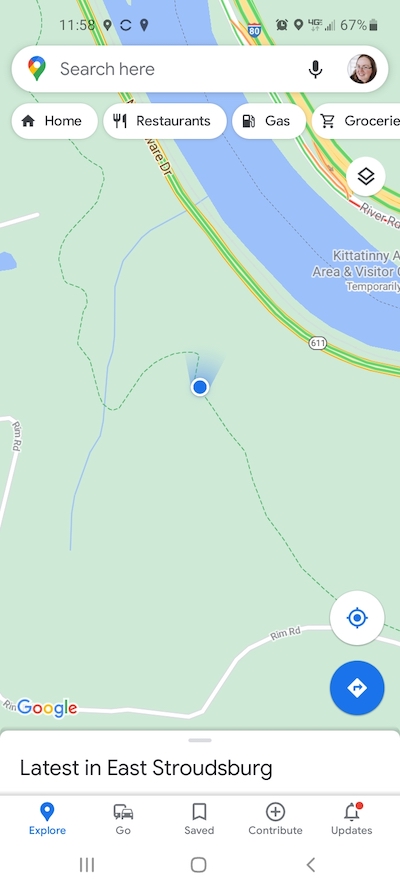

“Do you know how to drop a pin in Google maps?”

I tell her I don’t but that I can figure it out. She asks me to open Maps and take a picture of where it shows. I do that. Then I google “how to drop a pin android” because I do not have an iPhone, a question she asked. I drop a pin and text it to her. Ask her if that helps.

“We’re working on it,” she says.

I don’t know what is happening, but I know that something is in the works. While we sit and wait on the side of the mountain, things are happening elsewhere. I know we are not alone, even though I can’t see any evidence of that.

Eventually, Phil needs to pee. He walks himself to a more secluded place, then decides to stand for a bit. He puts his back to the sun which is just starting to hit the spot where he’s standing. He is feeling OK but still not great. We hear sirens and I wonder if they are for us. The NJ highway we saw from the overlook isn’t too far away. Maybe it’s sirens for something else.

Ninety minutes have passed. Our parents check in and I tell them that we’re still waiting. I forgot to mention that we were not just hiking in the Poconos but on the side of a mountain. Getting to us would take some time.

Another dispatcher calls me. Assures me that people are on the trail, trying to find the best way to get to us. He asks how the patient is. I tell him he’s the same, no worse, no better.

“Call us if anything changes,” he says.

I hang up. I look down the trail a bit. And then I hear voices. They’re almost shouting, certainly talking loudly. So many hikers have passed us that I’m not certain these are our people, but then I see that one of them is wearing a helmet. I leave Phil and the kids behind, getting closer to the voices.

“We’re up here!” I yell and wave my arms.

—

It is Saturday and I can’t sit still. There is work to be done and if I stop moving, then I won’t move at all for the rest of the day. This is my curse: do it all and do too much or do nothing. I have trouble living in between, balancing work and rest. The week behind me unsettled me, and I feel an urge to do things I’ve been putting off. There are the usual chores of laundry and dishes, of running errands to the library and the grocer store, but there is also a sense that it’s October now and the days are dwindling. I tell the kids that we’re going out to the garden to pick everything we can see and to pull up plants.

“Be ready in an hour,” I tell them.

In the meantime, I need to clean out the freezer. The one above the fridge. We have a chest freezer in the mud room and that one stays pretty well updated. The one in the kitchen has been forgotten. I vow to make broth from the poultry carcasses I pull out of the freeze while at the same time promising myself not to keep anything and freeze it “just in case” I’ll use it sometime. I toss bag after bag of unidentifiable foods I thought should be saved. I am a kind of pack rat when it comes to food and before too long, the freezer is clear and the trash can is full. I take out the trash, then wash my hands and dump the frozen carcasses into the crockpot. I quarter an onion, chop a couple of carrots and celery, toss in some garlic and other seasonings, and fill the whole thing with water. This time tomorrow, I’ll have a pot full of broth to strain and pour into jars and freeze.

I fold clothes. Start some laundry. Get dressed. And then it’s time to head to the garden. I love the garden, especially in summer. But when September hits and I’m back at work, the garden, the houseplants, they all take a backseat. It is only the second day of October, but it is time to call it (mostly) quits on the garden. The children agree to harvest the popcorn and shuck it while I pick peppers and beans and tomatoes. I pull up everything but the peppers and kale, hoping they’ll continue to color and grow. After an hour, the garden is tidier and we have a bowl full of mostly green tomatoes along with a box containing corn cobs that need the kernels removed. My hands hurt just thinking about the flicking action required to free the kernels.

I realize that I need to start writing about what happened at the start of the week. Writing is hard sometimes; it’s also therapy (which is hard sometimes). So I sit on the couch and I start to tell the story.

—

It is pushing 1 o’clock and suddenly we are surrounded by first responders. What had been a lonely wait was now a cacophony of concern. They go straight to Phil, take his vitals, radio to the rest of the searchers until everyone is accounted for. The kids and I fade into the background as they decide the best way down. Two fire fighters are manning a wheelbarrow-like basket–the means to get Phil down the mountain if he can’t walk on his own.

They decide to go up a little farther, where there might be an old logging road. We trek to another overlook and stop. The road isn’t there. The first responders take pictures from the overlook. Talk and laugh with each other. Their mood is contagious. They ask where we’re from. I tell them “Lancaster.” I say how we’ve wanted to do this hike for months.

“We just needed a few extra hiking buddies, so thanks for coming out,” I say. Humor is my defense against other emotions. I make light of the situation because I can’t bear to think of the seriousness.

They decide we’re going to have to go back down the way we came. They consult with Phil, ask if he’s up to walking.

“Take your time. We go at your pace,” they say. “We’re all here. You’re safe.” He says he wants to give it a try on his own feet.

The group splits up. The men with the basket lead the way, then a few others fall in behind him. Then Phil, and another fire fighter, then me and the kids. Then a half dozen others behind us. We make quite the spectacle on the way down. We pass a few hikers who must be wondering what is happening.

I’m in the midst of it, and I’m wondering what’s happening as we march down the mountain. The men surrounding Phil take care to help him navigate the rocky terrain. They keep him talking, offering to put the Bears game on their phones.

“I don’t know if that will help,” Phil quips. He has not lost his sense of humor, and I am relieved to hear him talking and joking with these men. They tell us their names: there’s an Ian and a Michael and they make sure we’re doing okay as we walk behind them.

We come to spot not all the way at the bottom of the mountain and one of the fire fighters goes ahead, off the trail, to scout a path that is quicker to see how overgrown it is. Others are talking with the EMTs who will meet us on the logging road with a UTV to take Phil to the ambulance. The path is clear enough and we leave the AT and make our way toward the road.

We meet up with the UTV and as suddenly as all these men appeared, they disappear. Ryan, who may have been with the NPS, keeps me informed. They are going to take Phil to the ambulance and check him out. It will be Phil’s decision to go to the hospital after that. The kids and I are to follow behind, walking the road till we get back to the parking lot. He will be there, as well. No one will leave until they are sure we are all taken care of. I kiss Phil, who is seated in the UTV, and we start walking. We stop briefly for one of us to pee in the woods then follow the road. The UTV is long gone and it is just us. We pass a few people and I wonder if it is written on our faces, these circumstances we are in.

I finally recognize the path we’re on and know that the parking lot is not far away. The ambulance is parked by the lake and Phil is already inside. The kids and I settle on a bench near the ambulance, waiting for information. Ryan approaches and asks for Phil’s ID. I don’t know where he put it. He packed his own bag that our daughter carried down the mountain. We shifted all our gear when the emergency happened. I give him my husband’s full name and date of birth. He tells me that the ambulance won’t leave without telling me what’s going on. We can go to the parking lot. There is more water in the car, and I am parched. I gave some of my extra water to Phil on the way down.

I notice the EMT getting into the driver’s seat and Ryan comes back to tell me that there is something off about the EKG and they advised Phil to go to the hospital. He told me where they were taking him and that he would be in the parking lot to give me directions if I needed them.

“It’s 7 minutes away,” he assures me.

The kids and I haul ass to the parking lot. The ambulance is leaving and I don’t want to be far behind. One emergency vehicle stops and offers us a ride to the parking lot, but it’s not far, and I want to keep moving. Moving my body keeps my mind from running away with me. I politely decline and we keep walking.

The scene that greets us when we get to the lot is straight out of a TV show. Emergency personnel mill around. Their vehicles fill the lot. I feel like all eyes are on us, but maybe that’s just not true. We go to the car and unload some of our things. I tell the kids to get in, that I’ll be right back. I seek out Ryan. I want the address to the hospital in my phone. I don’t want any delays or mistakes. I open Google Maps and he types in the address for me. Everyone wishes us well as we leave.

My daughter sits in the seat next to me, navigating. Between the two of us, we are trying to conserve battery. We have responded to some texts, but in the flurry of getting off the mountain and to the hospital, I have not kept people updated. We have no idea how long this will last. If all had gone according to plan, we would have been on our way home by now. We are not prepared for a lengthy stay.

—

It is Monday and I wake up not alone in my bed but not with my husband. In the middle of the night, my daughter has come in, saying she had a stress dream and couldn’t go back to sleep, so I invite her to curl up next to me. Both of us were awakened from sleep–me by a car alarm in the parking lot of the apartment complex next door; her by a stress dream involving oversized bunnies chasing her.

It is 5 a.m., my usual wake-up time for a work weekday. Today, I will not go to work. I will get the kids to their buses so they can go to school, then I will go back to the hospital we left less than 12 hours ago.

—

It is nearing 2 p.m. We walk into the ER and I approach the desk. They ask how I am, and I don’t know how to answer.

“They brought my husband in by ambulance earlier,” I blurt out. I like to get right to the point. The woman at the desk asks his name, types on the keyboard.

“Oh, they brought him in like 2 minutes ago,” she says. I am relieved that we weren’t far behind. She says they’ll get him settled and then we can go back.

We brought only a few things in with us, and I’ve had to pee for an hour or more, so I park the kids in the waiting room and I go use the bathroom. I’m still running on adrenaline. I can feel it in my body. I’m barely aware that I smell like bug spray, have sunburn on my face, or that my hiking boots are heavy on my feet. I wash my hands, look at myself briefly in the mirror and brace myself for whatever comes next.

What comes next is more waiting. I use the time to update people on what’s happening. I text our parents, our pastor, some friends. I look for contact information for my husband’s boss. I compose an Instagram post that will cross-post to Facebook to let people know what’s going on. Because we are alone, two hours from home, and I have to know that we aren’t forgotten. This communication keeps me busy. I don’t know how much time passes. Other people come into the ER. The TV plays some kind of home renovation show. At one point, we go out to the car to get some water bottles, books and games we brought for the car ride.

The nurse whom I first spoke to at the desk asks my kids’ ages. I tell her: 13 and 11 (almost 12). She wrinkles her nose. The hospital visitation policy during COVID disallows visitors under the age of 12. She sets out to see what she can do. No one will bend the rule for us. Our son isn’t eager to go back to see his dad, anyway.

So, I leave them together in the waiting room and try to follow the directions to his room in the ER: a left, a right, another right. I arrive as someone is taking his demographic information. I don’t know if I should go in or not. I call out, “This is my husband. Can I come in?”

And there he is, propped up in a bed, hooked to machines. The woman taking his demographics leaves, and Phil and I recap what we know. The EKG is wonky. They’re testing his blood. They might keep him overnight. I ask if he wants things from the car. I leave and bring him a few things to keep him company. I want to stay and I want to go. I am forever torn by desire to care for my husband and care for my kids. How can I ever do both at the same time when there is only one of me?

Here is where the memories blur. I go back to the waiting room. I buy the kids snacks from the vending machines. Vending machines that take debit card are one of the world’s best inventions. They eat sugar and drink tea. I keep sucking down the water because I didn’t have enough during the day. I start to wonder what our options are. We are getting an education in the ER, watching all kinds of interesting cases come in the door. Our phones are losing power. We need to eat real food. There is no telling when or if they are going to move Phil.

We wait another hour maybe. I go back in to talk to Phil. The doctor wants to keep him overnight and run a stress test in the morning. His EKG readings are still abnormal. I say what I don’t want to say.

“We have to go home. I have to get the kids home.”

I start to cry a little, thinking about leaving Phil overnight, even though I know he’ll be in good hands. I say “good night.” Promise to be back tomorrow. I go back out and tell the kids we’re going home. We pick up our mess. Use the bathroom. Fill our water bottles.

Back in the car, I am girding myself for what comes next. First, we find dinner. Hot food. Doesn’t matter what. Then, I drive the 100 miles back to Lancaster. Our daughter sits in the front seat again, navigating. We don’t want to run the GPS because it will drain the battery. I have a general idea how to get home. But first: food.

We get back on the highway and I take the first exit that promises food, but it’s all diners and sit-down places. We need a drive-through. We keep driving on the road where we exited and end up back almost where we started. But there’s a Wendy’s, so we head for it and get in the drive-through. As we pull up to place our order, another car pulls next to us and the older man behind the wheel rolls down his window.

“Do you know how to get back to 33?” he shouts.

“I don’t. I’m sorry! I’m not from around here.”

Maybe he thinks I’m lying. Meanwhile, the person trying to take my order on the other side of the drive-through speaker is asking me to repeat myself.

“I need a moment, please,” I say. It is true for lots of reasons. The kids decide what they want. We order. We pay. We get back on the road and begin dashboard dining as we drive into the setting sun.

When we finish our food, I ask my daughter to text my mom. She wants to talk to us, and it’s easier for me to pick up with Bluetooth if she calls me. We talk to my parents for part of our drive home, and it is calming, even though they overhear me talking to other drivers. I do this when I’m nervous. I hate driving long distances. I am sometimes a jerk, making comments about other people’s driving behaviors. I realize I have never driven this far alone with my kids before. I am too afraid to take them too far from home myself.

Another first for the day.

We walk into our house around 8 p.m. We all need showers. I need to make plans for Monday. Call off work. Find someone to be with the kids after school and pick up from practice. Unpack a few things. Pack a bag for the next day. I am still running on adrenaline, although it’s fading, now that I’m home. I’m ready to crawl into my bed but there is still so much to do.

We shower. The kids watch YouTube for a bit. I email their teachers to let them know what’s going on, to say that my kids might not be themselves at school the next day. Please, I beg, offer them grace.

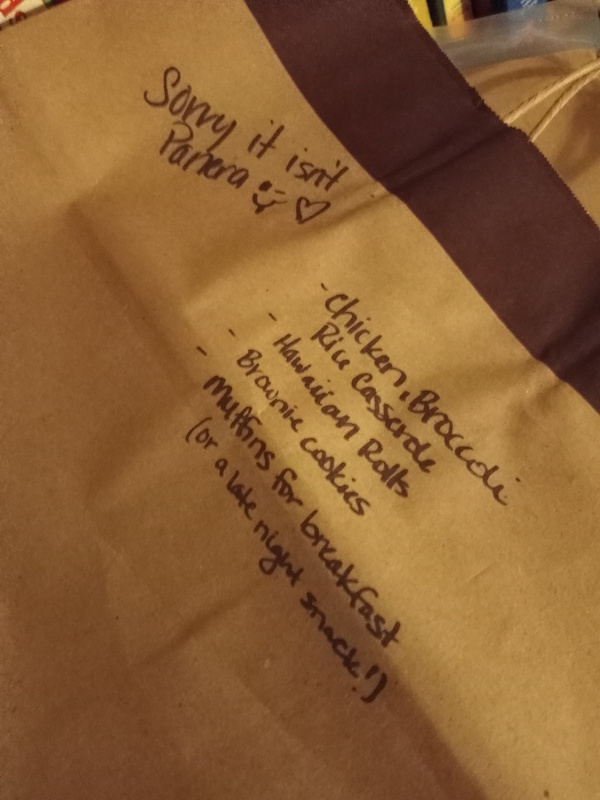

A friend offers to be on kid duty, bring dinner and stay the night if necessary. I am relieved.

It is 9 p.m. and the kids are in bed. I tell them how proud I am of the way they handled the day. All day, we were teaching them things.

“It’s okay to ask for help,” I say on the side of the mountain while we wait for the emergency personnel. “Even if this turns out to be nothing, we did the right thing.”

And then, as they’re going to bed, I say, “it’s okay to be sad. To cry. I’m going to go to my bed and cry and it’s not because I think Daddy isn’t going to be okay. It’s just been a lot to take in today. So don’t worry if you hear me crying.”

I do exactly what I said. I crawl into bed. I pull the covers tight around me. And I sob. I let out all the things I’ve been holding all day. Earlier when my mom asked me how I was doing, I said, “Crumbling after holding it all together all day.”

—

I have a complicated relationship with my faith these days. I don’t know how to interact with God right now. Earlier this year, we left a faith tradition that was almost the only thing we knew when it came to spiritual life. I feel like I’m rebuilding. Unlearning some things. Prayer, faith, belief, worship–none of it comes easy to me anymore.

All day long, people have said they are praying for us, and I believe them. I am strengthened by their thoughts, prayers and encouraging words.

Alone in my bed, with just me, I struggle. I complain out loud (to God?) that I can’t do this. It’s too hard. I want to yell “why?” but I find that question pointless. I don’t think there are answers to why things happen the way they do. Things happen. Period.

So I’m surprised when a Bible verse pops into my head. It is not just a verse but words recorded as being spoken by Jesus, and in that moment, I feel like He’s speaking to me.

“Do not let your heart be troubled,” He says. “Trust in God. Trust also in me.”

I don’t bother trying to remember a verse reference or whether that’s exactly how it goes. I accept the words of comfort. And finally, I sleep.

After the car alarm wakes me up, I find my mind racing with a list of items I need to pack, so I get out of bed and make a list and then my daughter joins me in bed.

While the kids get ready for school, I clean out the car. Take out the garbage. Do some laundry. Pack the bags. Fill water bottles. I check in with Phil a little after 7 a.m He spent the whole night in the ER because no beds were available. Just before I head out, he texts me that he’s been moved to a different part of the hospital, that his stress test is scheduled for 11:30. I look at the clock and figure I’ll make it with plenty of time.

But I don’t count on traffic. Or my need to stop and pee. Or how difficult it is for me to figure out where to park. And how long it will take for me to find him when I get there.

On the drive up, I call my in-laws to talk. Then after a pit stop, I call another friend. I need to talk, to tell the story, to keep my attention on something besides all the traffic and my rush to see Phil. I park in a lot less than a block from the hospital, but I’m carrying two backpacks (one for me, one for him) and two water bottles and a purse. I look like I’m moving in. I’ve already decided that I’m not coming home without him. If he stays another night, so do I.

At the front desk, they take my name and the patient I’m there to see. They call up, I’m not sure why, but I’m allowed to go. They direct me to the elevators. I wait as a patient on a bed is loaded into one elevator, then wait again for an elevator to come for me. I get in. It stops on the second floor and a hospital worker gets on.

“You’re loaded down,” he says. I explain that my husband spent the night. That we’re two hours from home.

“Not the vacation you planned,” he says. I shake my head. Get off at the next floor. And I make my way to the Rapid Treatment Center where Phil sits in a bed behind a curtain. At least there are windows. And only a few patients. It’s relatively quiet.

I get his phone charging and hand him some things. We talk and catch up on any medical news about him. It is only about 15 minutes before they start prepping him for his stress test.

“You’re going to disappear for about 2 1/2 hours,” his nurse, Tom, says. I ask if I can go and Tom immediately says, “No, not to nuclear medicine.” So I gather up my things and head back to the car. It is nearing noon and I need to eat. I’m looking for somewhere I can hang out for an extended period of time. The closest Panera is not too far away, so I go there. But it’s drive-through only when I get there and the line is long. I decide to try somewhere else.

I head back into town, toward a cafe that promises a courtyard but when I drive by, it looks like they’re only serving from the window. By this time, I am super hungry and super annoyed that this is all happening in a pandemic when nothing is normal. I go back to the parking lot where I started, having done nothing but kill 30 or 40 minutes. I grab my backpack and head toward the deli across the street from the hospital.

It is a small place, but it is open for dine-in and the menu is extensive in the way of sandwiches and wraps. I am greeted warmly and I make my choice: a wrap with grilled chicken and avocado and other filling ingredients. What I really want is a bagel but I also have a complicated relationship with gluten sometimes. The person taking my order keeps calling me “miss” and this brings a small smile to my face, hidden behind my mask. I am near a college, so I pretend that with my backpack slung over my shoulders, he thinks I am a college student. There is too much gray in my hair for this to be true, but I cling to the altered reality for a moment.

I sit by the window and wait for my name to be called. I can see the hospital from my seat. A few medical employees come in and order, so I know the food must be decent. They call my name and I get my wrap and sit back down.

I notice that FoxNews is on the TV, but it doesn’t bother me. I’m not interested in anyone’s politics at the moment. I eat. I check my phone. Post an Instagram/Facebook update. Someone who works in the deli sits down to eat and is paying attention to the news, making disparaging comments about the president. I keep my head down and eat. I’m wearing a shirt that says “We stand with our neighbors,” a message of support for the refugee community in Lancaster. I wonder if anyone notices. The deli is getting busier and I’m in no hurry to be anywhere else but I don’t want to be here anymore.

I finish my wrap and head outside. The university is across the street and I always feel conflicted about walking around public universities. Am I trespassing? Am I welcome? So I stick to an outer boundary sidewalk and talk a little walk. I don’t want to go back to the hospital and wait for Phil, yet, and I need to keep moving my body. After a short walk, I have to pee and I need more water, so I head back to the hospital. It’s 20 or so minutes before the earliest time Phil could be back, so I head back to his pod. I answer some texts and messages. I log in to my computer. I charge my phone.

Eventually, I pick up a book I brought along. For some reason, I have trouble concentrating on reading when I’m waiting for something–like boarding time for a flight. I can’t fully relax and let myself slip into the story, but it does pass the time and eventually Phil is back from his stress test and Tom, the nurse, is getting Phil’s diet order changed so he can eat a real lunch. It is after 2 o’clock and Phil hasn’t eaten much for the past two days.

It is time for more waiting. We talk a little. I fret. Sitting still is not my forte. I want to go/do/act but there is nowhere to go, nothing to do, no action to take. We keep hearing that the cardiologist is not available to read the stress test until 4 o’clock. That’s more than an hour from now.

I take a short walk to the bathroom and find a water fountain to fill my water bottle. The nurse has offered my bottle water.

“You don’t want to drink our water,” he says. But I find that it tastes like river water, which simply tastes like home, the one in Illinois.

A customer relations representative stops by, offers an apology and a mask for the delay in getting him a room the previous night. I get up to take another walk and overhear that the cardiologist has read the results for another patient, so I head back to the pod and wait. Finally, the attending doctor arrives, tells us the stress test was normal and they don’t see anything requiring a more invasive procedure. He will be released tonight. I text the news and take a phone call from a friend in Arizona while I head downstairs to see if the cafeteria is open. Phil has ordered dinner, and if he gets food, I want to eat something, too. I don’t know how long it will take to discharge him.

I talk as I ride the elevator and wander the basement with a helpful hospital employee. The cafeteria is not open until 5 p.m. and I am not interested in vending machine food, so I ride the elevator back up. Phil’s nurses get on at floor 2, tell me he’s being released. I nod, still on the phone with my friend. We all exit at floor 3 and I go back to the pod, give Phil the food update.

It is not long before they work to unhook him from machines, go over his discharge paperwork, give him time to get dressed. I start gathering our things and before we know it, a wheelchair is waiting for Phil and we are being escorted out of the hospital. I leave Phil and the attendant at the main entrance to walk the block or so to get the car.

Then, we are on our way. We speak briefly of dinner but we both want to keep moving toward home before we stop again. We are not running GPS because I think I can find our way home, but I miss a turnoff and don’t recognize the road we’re on. Phil guides us via his phone and we take a different way home. We are on a bypass, high in the mountains, and the trees are just starting to change. There is traffic, but it is less than what we might face around Allentown, so maybe it was okay that we took this detour.

We make it to the Sheetz that is our familiar pit stop by now and I text my friend at our house that Phil and I will not make it home for dinner. We will need to stop and eat something before then. We place an online order for Chick-fil-a in Reading, maybe 15 minutes away. Then we get stuck in traffic, and I just.want.to.be.home.

We sit in the drive-through at Chick-fil-a, get our food, and I eat it too fast, but we also ordered milkshakes and I don’t care if I get a brain freeze. I wouldn’t mind a complete mind-numbing for a day, but I still have to get us home.

When we finally pull in the driveway, it’s almost 8 o’clock. We say goodbye to our friend and I get the kids to bed before falling into bed myself. I am more tired than I thought possible, than I can remember being in a long time.

But we are all of us home.

—

I take Tuesday off because I don’t want to let Phil out of my sight. And we’re both tired. A day of rest will do us good and that’s what we have. A friend brings dinner and we eat it after I pick up our daughter from her field hockey game.

I decide to take Wednesday off as well. Phil has a doctor’s appointment late in the afternoon and a haircut midday. He is feeling okay but I’m not ready to let him go out on his own yet. And I want to be there for the doctor’s appointment.

So after my run and a shower and some lunch, we head downtown. I park at the library, return some books, pick up two I had on hold and then we walk together to the barber shop. I leave him there and walk over to the shops on the 300 block of North Queen. I want to buy thank you cards and my go-to place is on that block. I find what I’m looking for and make my purchase with time to spare, so I head farther up the block to a collection of shops inside one building. I wander and just look and shop. Nothing in particular catches my eye, but it is a way to pass the time.

I head back toward the barber shop just in time for Phil to be walking out. We head back to the car, make a brief stop at home, then drive to the doctor’s appointment. The same friend who helped us on Monday is coming back this afternoon for the kids because I don’t know how long the appointment will be. And another friend is bringing dinner. We are well cared for and I still can’t comprehend it.

I’m not sure if they’re going to let me go into the appointment with Phil. I have steeled myself for the possibility that I will have to argue for my presence, but no one says a word and I am with him for the entire appointment. The provider is thorough. He will check some things in Phil’s blood, do a sleep study to see if sleep apnea is affecting his health, and refer him to a cardiologist. He prescribes some medicine for anxiety. They do another EKG just so they have one on file since the communication between their office/system and the hospital where he was admitted is not seamless.

“You are safe to return to work,” he says. We leave with no answers but some hope that we are on the path to figuring out what is going on. It is frustrating, though, to not know what caused this episode, to be left wondering if it will happen again.

—

It is Friday and my hair is streaked with pink. October 1st marks the beginning of Breast Cancer Awareness Month and the principal at our school annually participates in the Real Men Wear Pink campaign to raise money for this cause. He invites everyone on the first day of October to wear pink along with him. So in addition to my pink shirt and pink boots, I have borrowed without asking my daughter’s pink hair chalk.

It’s not that I need attention; it’s more that I need to have a little fun. To bring a little joy into the world. Pink hair feels like an easy step.

I went back to work on Thursday. So did Phil. But Friday is his first full day and I worry most of the day. He texts me that he’s feeling mostly good. Later in the day he says his throat hurts a bit and he has a headache. He comes home a little early, has reduced hours for Saturday so he can get some extra rest.

By Saturday night, I feel like we have lived an entire life in just one week.

—

I still tremble when I think of what happened on the mountain. My body begins to react as if I am still living through it. My heart races and my blood pressure rises and I have to remind myself to breathe. I have to take breaks while writing just to pull myself out of the memory.

It was terrible, what we went through.

And we have so much beauty to remember.

The setting of our trial was breathtaking, and someday, I wan to go back.

Friends and family rallied around us, supporting us from near and far. We have spent more than a decade building this network of support, an ongoing process, and it is comforting to know that it holds.

The first responders were not only well-trained to find us, they were kind and compassionate. Not one person made us feel like we’d done something wrong or that this was an inconvenience to their Sunday afternoon. I don’t know many of their names, but I feel like we are bonded for life.

Our kids were flexible and resilient, which doesn’t mean they were perfect. We still had challenges this week as they sorted through their emotions and varying stressors. I would not choose different kids to go through this life.

It is easy sometimes to focus only on the terror. To remember and relive the worst parts of the week. So I’m trying to pair those memories with the beauty and the good, as well. Both were present.

Always, in this world. Beautiful and terrible, together.

I’ll try not to be afraid.