There are bruises on my body I can’t explain. Days after leaving the hospital, I discover one on my sternum, a yellowing circle that is tender to the touch. Was it because my husband rubbed his fist across my chest to try to revive me when I passed out in the hallway as our daughter called 911? Did they have to administer chest compressions when my blood pressure plummeted in the ICU? Is it because I was on a life-support system for a day that drew blood out of my body, away from my heart, into a machine that oxygenated my blood and sent it back?

There are no clear answers.

It’s a theme I have to live with right now as my body recovers from a harrowing experience I never saw coming. (Can we predict any harrowing experience in our lives?) I’m a planner. I like to believe I can see trouble on the horizon, but I’m no clairvoyant. Trouble finds us and sometimes we’re blind to its approach.

//

In case you missed it, here’s what happened, to the best of my recollection:

On Friday May 12, I went for a training run after school. I’d been slowly working my way through a Couch-to-5K program to get my body back in some kind of running shape, and this was the next session in the program. But I couldn’t do it. Every time I tried to run, I couldn’t catch my breath. I had to walk most of it, and when I got home, I felt like I might pass out.

I recovered, though, without incident. I checked the weather and the air quality was bad–like orange alert bad–and it was hotter than I was used to, so I chalked the whole thing up to rotten air quality (a “perk” of living in Lancaster County) and tried to move on.

Except that for the next four days, I became breathless doing simple things, like walking down the hallway to the bathroom at school. I couldn’t walk and talk to Phil as we traveled the trail around the school while our kids were at practices. On Tuesday, it was bad enough that I decided to cancel my next day of work and make a doctor’s appointment.

//

Wednesday, May 17. I’m at the doctor’s office. I’m not in any pain, I just can’t catch my breath when I exert myself. Resting is fine. My primary care provider listens to my lungs, which sound a bit diminished in capacity but nothing overly concerning. She does an EKG, which comes out normal. She prescribes steroids and an inhaler to reduce the inflammation in my lungs and promises that if it gets worse, we’ll do a chest X-ray. I fill the prescription and take the steroids.

I spend the rest of the afternoon resting, grateful that it isn’t something more serious. I make dinner and my son wants me to be the one to run him to his sports practice. I’m struggling a little bit to breathe, but I think it’s mostly because of the effort I’ve put into dinner. Besides, the school is 5 minutes away. I’ll be there and back in no time. I get him to practice and on the way home, I start to feel not right. I will myself to make it home. I almost sit in the car for a moment to catch my breath but our neighbor is smoking outside and the smoke stings my lungs. So I stumble inside. I drop my things, bent over, trying to get air. I am going to pass out, so I call out, “Phil, I’m not OK” and I sit down in the hallway.

When I come to, Phil is rubbing my chest and our daughter is on the phone with 911. I am soaked in my own urine but I refuse to move until the EMTs arrive.

“You turned blue,” Phil says, and I try not to focus on the fear in his voice. He is my steadying presence. When he’s scared, the situation is scary. I look at my daughter projecting calm as she speaks confidently into the phone directing the ambulance to our house.

I hear the sirens and then there are two EMTs crowded into our narrow hallway and I am no longer in control of my body. They pop an oxygen monitor on me and I’m reading at 88 percent. They help me sit up and the pulse ox dips to 83 percent. I barely register this as they hook me up to oxygen and ask me questions about what happened. They take the information and make a plan. They are calm and confident. I am scared and uncertain.

“Are we okay to go to the hospital?” the lead EMT asks.

“Yes,” is the only answer that makes sense.

I change my clothes, with their assistance, while sitting in the hallway so at least I am dry when I make my ride to the emergency room. I leave my shoes behind. The two EMTs carry me in a chair out to the ambulance, transfer me to a gurney. One climbs in the driver’s seat. The other climbs in with me and continues to ask questions and monitor. She is almost certain she knows what is wrong with me and her words terrify me. They will be confirmed later, but for now, I hope to God she’s wrong and that this is a huge misunderstanding. Somehow, I think, my body has just overreacted to something simple. Maybe I’m allergic to prednisone?

I watch the city pass by through the back doors of the ambulance as the EMT starts an IV while we drive. I have an EKG as we travel. First responders will never cease to amaze me. The lights and sirens are not going, so maybe it’s not an emergency after all. I’m awake. Conscious. I know what happened to me, why I’m in the back of this vehicle.

They roll me through the hospital hallways. It is now almost 7 o’clock, shift change. It’s been an hour since I passed out. They take me to a room and a nurse sets me up. At some point, my daughter arrives. She is 15 and is my sole support in the moment. Phil dropped her off so I wouldn’t be alone while he went to call my parents and pick up our son and try to create a somewhat normal routine for him. The time in the ER is a blur. I am poked with blood draws and an IV, still on the oxygen. Monitors show my blood pressure, my oxygen levels, my heart rate. I have several EKGs. I talk with my nurse. I speak with a doctor. She orders a CT scan.

One of my toxic traits is the ability to dissociate when a situation is painful or uncomfortable. It serves me well in this circumstance. I barely register that I’m being wheeled into another part of the hospital and transferred to the CT bed. I close my eyes and hold back tears as I listen to the machine’s commands to “stop breathing” and “breathe.” I shake a little as the contrast dye goes into my body, flushing me with warmth and the sensation of needing to pee. In a matter of minutes, it’s over, and I’m back on the bed, being wheeled back to my room.

In my absence, my daughter has answered questions for a case manager, and I want to cry because she’s 15 and shouldn’t have to be the adult here. Not more than a few minutes later, the doctor appears at the entrance to my room and proclaims that I have multiple blood clots in both lungs and to expect a bunch of people to descend on my room. And then I hear my room called over the loudspeaker. Did they say “heart to ER 149”?

I start sobbing because I am so, so scared, and my daughter reaches across and holds my hand. I hate that I can’t be strong for her, but I also know that I can’t fake what I’m feeling. Blood clots in my lungs sounds serious and I don’t want to die.

I get another EKG. I talk with a provider from the pulmonary team. I think they start me on some kind of clot-blasting medicine immediately. They are moving me to the ICU as soon as possible. My husband and son arrive but are told only one person can come back. Our daughter prepares to switch out, but I tell her to find my nurse, who promised she’d get my whole family back here if needed.

They all arrive in my little room just before I get moved to the ICU. We take separate elevators but meet on the 6th floor, where I ask about the view. I surprise myself with my good spirits in spite of the circumstances. The medical staff send my family to the waiting room and promise to come get them when I’m ready.

I arrive in my ICU room and am immediately stripped and bathed by a team of strangers. Again, I retreat into myself as they scrub every inch of my body to reduce the chance of infection. When I am clean and gowned, I ask for water. I didn’t eat dinner and my mouth is parched but no one knows if I’m having a procedure in the morning or not, so they give me very little. We talk about what is happening and finally my family comes in. It is a school night and we are all up later than our bedtimes, so around 10:30, I send them home, knowing it’s likely no one will go to school or work the next day.

I’m finally allowed some chocolate ice cream. I post a picture and update to social media, asking for thoughts, prayers, good vides, positive energy because I am in a very scary situation and I need support.

In less than an hour, the very scary situation becomes even scarier.

//

“She doesn’t get eaten by the eels at this time.”

I recently re-watched The Princess Bride, my favorite movie, and what I’m writing reminds me of how the grandpa breaks in to assure his grandson that the princess doesn’t die at that point in the story. The boy is clutching his sheets, not nervous, just “concerned.” The grandpa tells him they can stop reading anytime, but the grandson wants to go on.

I’m still here. It’s what I kept telling people afterward. You can stop reading now if you want, but I’m going to go on.

//

The next part is somewhat of a blur. And I can only tell it how it felt to me. I’m not making a blanket statement about bodies, souls or what happens when those two things separate.

I remember starting to feel lightheaded. And then I was sweating profusely. I hit my nurse call button, and my symptoms were worsening. I hit the button repeatedly. I wanted to call out for my nurse, but I don’t think I did. She, and others, arrived. I couldn’t really see them. My vision was blurred. I could feel them touching me, laying me back, commenting on the sweat. I felt like I was losing connection with my body. I could sense things going on around me but nothing was clear. I don’t know how long this went on. I don’t know if this is where the bruise on my sternum came from. All I remember is that they gave me oxygen and I was back from wherever I had started to retreat. I think I said, “I feel better.”

I won’t call it an out-of-body experience but I will say I felt separate from my body. Do with that what you will.

They called the heart doctor at home, got him out of bed. There may have been dozens of people in my room or in the hallway. In the days to come, nurses and aides assigned to me would say, “yeah, I was here Wednesday night. You were a trooper.”

At some point, someone told me that my blood pressure dropped to 55 over 30 and they were sure I was going to go into cardiac arrest. Oh. Oh! When everything is happening to you, you have no idea how serious it is. When I think back on it now, I’m convinced my body tried to give up on me. I think I could have died that night. They called Phil to tell him what was happening.

The doctor arrived and laid out the plan: we could do nothing and hope that the medicine broke up the clots and that my heart and lungs could handle the work of keeping me alive. OR we could hook me up to a machine that would do the work for my heart and lungs, to give them a break, and see how that goes. “Full life support,” he said at some point, but that didn’t really register. I know now that what he was proposing was putting me on an ECMO machine and that this, too, was quite serious. In the days that followed, anyone who heard I was on ECMO would react with strong surprise.

He asked if I was able to consent to the treatment. I said yes and signed the papers. He called Phil, too. I had a basic understanding of what would happen, and I would be awake for all of it with just some sedative to keep me calm and from feeling pain.

My nurse, Audrey, put herself right in my line of vision. “I’ll be here when you wake up,” she said. She would be the first of several nurses I will not soon forget.

Skip the next part if you’re squeamish about medical things. I usually am, but maybe it’s different when it’s happening to you.

When everything was done, there were tubes in my groin and femoral artery and veins transferring blood out of my body into this machine to oxygenate it and send it back into my body. It was something like 2 a.m. and we weren’t sure if I’d have a procedure in the morning so I wasn’t allowed to eat anything.

I wasn’t about to get out of bed anytime soon. I learned to pee in a bedpan, which took some practice and maneuvering. I tried to sleep. I was worn out from the day and unsure what would happen next. I didn’t know that most people on ECMO are not awake for it. I didn’t know that ECMO is sometimes? often? a last resort.

What I didn’t know wouldn’t hurt me.

//

The flowers I received in the hospital are wilting, marking the passage of time. Physical wounds heal faster than mental ones. As I write this, my bruises are fading. I’m gaining strength in my legs. My lungs fill to capacity with air. I’m feeling more capable of doing things, with rest time afterwards.

My mind is another story entirely. I fear a return to the hospital. I worry about what other unseen, unknown dangers are coursing through my body. I grow anxious thinking about how in so many ways, this could have gone so much differently (in a bad way). I could have been alone. I could have been driving. I could have been at school.

I don’t actually fear death (but I don’t want to die). I fear what my death would mean for those I leave behind.

My body will heal in time. So will my mind.

//

I posted an update to social media and slept as well as one can when attached to multiple machines with tubes poking out of seemingly every orifice. I haven’t even mentioned the A-line in my right arm and my immobilized right hand for the multiple-times-a-day blood draws that turned my forearm various shades of purple.

The next morning–Thursday–my pastor (she’s also a friend) showed up at 6 a.m. to sit with me. She didn’t leave for almost four hours and it was the most beautiful gift I didn’t know I needed. I wasn’t alone when the doctors began to arrive discussing my next step. First, the interventional radiologist (I will probably get titles and specialties wrong) wanted to do a thrombectomy to try to suck the clots out of my lungs. That meant no food until the procedure later in the day. I was bummed but willing to do whatever it took to get better.

I texted Phil and resigned myself to another day without food.

And then my first piece of good news arrived in the form of a heart surgeon whose initials would eventually be written on my leg. After consulting on my case, he and a couple of others decided to let me sit on the ECMO for a day and do scans the next morning to see if my heart and lungs had recovered. I could have kissed him because this meant I could eat. And spend the day relaxing and visiting and letting my body and the meds do their things.

Because it was almost mid-morning by now, the food wasn’t great, but I didn’t care. It was something to eat and I relished every bite.

Phil and the kids stayed home from work and school. My parents decided to head to Pennsylvania from Illinois. Visitors dropped in at various times of the day, lifting my spirits. It was a bit exhausting, but it was a day of just being. A calm before any more storms. A brief reprieve between the hurt and the healing.

I went to bed that night knowing my parents were almost in town, my family was being taken of care by church and work friends, and I’d have a 6 a.m. date with the CT scanner the next day.

My spirits were high. My body was tired. My hopes were tentative.

//

Friday, May 19. Around 2 a.m., my nurse reluctantly gave me a cup of water but told me to sip it. When his replacement came later that morning, she took the cup from me because we didn’t know if I’d be having a procedure later in the day.

People began to assemble around 6 a.m. to move me and my ECMO from the 6th floor to the ground floor where the CT was. It was a terrifying experience for me because of all the movement. Nothing hurt, but I was scared to be leaving the safety of the ICU. And I was picking up on some interpersonal conflict between some of the staff. Empaths miss almost nothing. When I got to the CT room, it was announced that I’d have to go in the scanner head first (as opposed to feet first) because of the machine I was attached to. I was crying by this time because I was just so overwhelmed and scared. We got through it and then I was cramming into the elevator again with 3 or 4 other people managing all my extra attachments, and I was never so glad to see my ICU room as I was when we got back.

I’d have to wait a bit before I’d get the results and in the meantime, I needed another ultrasound of my heart to see if the right ventricle had recovered enough to go back to doing its job. The heart doctor seemed encouraged, and the CT scan showed the clots had mostly broken up. There was still debris in my lungs but the massive embolism that had sent me to the hospital was no longer evident.

This all meant I’d be taking another field trip later in the day to the OR to disconnect me from the ECMO. No food (are you sensing a theme?) until it was over.

Phil arrived and I cried and vented about my morning, then I fell asleep because I just couldn’t deal anymore. It was a long wait for the heart doctor to finish a previous operation and be ready for me. An anesthesiologist came in to see me. I would not be put under for this procedure either, just given sedatives to dull the pain and my awareness.

When the time came, this trip was smoother. The bigger elevator goes to the OR on the second floor but not to the basement for CT, which seems like a design flaw in an otherwise state-of-the-art hospital, but I’m not an architect or engineer so what do I know?

I was blissfully unaware of most of what was happening. When I did come to, the operation had been a success but one of the openings was still bleeding. They’d been applying pressure for almost an hour, so I’d been in the OR longer than expected. They rolled me back up to my room and I finally got to eat. More monitoring, more rest, but fewer supports felt like progress.

//

I took this picture from my bed in the ICU.

I called it “Still Life.”

Still Life, as in the art term for depicting inanimate objects.

Still Life, as in I’m still here.

//

I’ve never had to pay this much attention to my body.

Breathing? Yes.

Does it hurt? No.

Oxygen levels? Normal.

Blood pressure? Normal.

Heart rate? Elevated. But that could be anxiety.

Incision site? Draining a little every day. I examine it closely unsure what I’m looking at or looking for, hoping that it’s okay.

Light-headed? No.

I’m exhausted by a trip to the kitchen to make my breakfast. I can’t find a truly comfortable sleeping position that doesn’t increase my anxiety because something hurts as a result. I’ve walked to the backyard. I’ve sat on the porch. My world is small right now. How will I know when I’m comfortable expanding it?

For years during the early stages of the COVID pandemic, I lived in fear of the virus killing me or those I loved. We’ve survived so far, but now I fear that my regular ordinary life might also kill me. How do I go on living having come so close to death?

//

On Saturday I got out of bed for the first time in days. I sat in the chair to eat breakfast. I peed in a toilet instead of a bedpan. I still needed to have a suture removed, and because of the bleeding during the operation, I was to be on bed rest afterwards. So I tried to enjoy my limited freedom of sitting up.

While I rested and lounged in the ICU, my family bought our garden plants and my dad put them all in for us. The garden is one of my summer joys so to have it done and not delayed was a gift.

My transfer orders out of the ICU came in late Saturday night; I just had to wait for a bed to open up. That happened Sunday morning, just as my parents were leaving to attend my son’s all-day lacrosse tournament. I said goodbye and thank you to one of the nurses who had been with me multiple days. I moved to a different room on the same floor. I bathed myself and sort of washed my hair for the first time since entering the hospital. I lay in bed without being attached to any machines. I still had to call a nurse when I was ready to go to the bathroom, but I could get myself there and back without assistance.

This was the day it started to hit me, how much I’d been through and how far I’d come. I was ready to be on my own schedule but also not ready to move the caregiving responsibilities to my family.

//

There were a flurry of people in and out as I settled onto the floor (as opposed to the ICU; hospital lingo, I guess)–friends, an occupational therapist, a physical therapist, nurses, aides. I took a short walk with the physical therapist about three doors down the hallway. I started to feel light-headed so we went back. My oxygen levels were good afterwards. It might have been anxiety, a theme that would pop up repeatedly in the coming days and weeks.

//

“You’re a good candidate to get out of here.”

The internal medicine doctor stopped by early Monday morning and I was actually relieved to hear those words. I wanted to know I was progressing, showing improvement. It’s hard to compare where you are with where you think you should be when you’ve come through something traumatic. I kept focusing on the fact that I was alive. Everything after that was a bonus, even if it takes time.

I got to eat a salad, a treat a lot of patients don’t get to order. This was a highlight of being out of the ICU.

I had a date with OT and PT in the gym in the afternoon, my first field trip since the ICU. The OT took me through some routine activities I’d need to do at home, like dressing myself and stepping into the shower, reaching for things in the kitchen cabinets. She gave me the advice I’ve been trying to follow ever since: “Listen to your body; not your mind. Because your mind will tell you that you can do more than you’re ready for.”

The PT guided me through navigating steps–there are four into our house–and I practiced stepping on and off a curb. We walked the gym and I did some leg exercises. She sent me with homework. I was cleared by both to go home.

Things moved pretty fast after that. My discharge papers were in process. My prescriptions sent to the pharmacy. I could change into my own clothes. Phil left work early to meet me at the hospital and start carting our stuff to the car. While I waited for my official release, I was scrolling the website for my medication to find the discount card. There’s something wrong with a healthcare system that CAN offer a discount on life-saving medication but places the burden on the patient. I was literally in my hospital room waiting to be released after spending four days in the ICU (five days total in the hospital) figuring out how to get the pills for less than $150. The is not the kind of stress a recovering patient needs.

And then it was over. I was wheeled out to the car and on my way home.

Really, it was just beginning.

//

The days at home sometimes make me miss the hospital. It’s easier, in some ways, there. Fewer hoops to jump through. Phil has spent a total of 2 hours at the pharmacy trying to get the meds I need. For the first few days, my parents were still in town, ready to meet any need I had. I made follow-up appointments–so many phone calls and if you know me, you know how much I dislike phone calls–and went to follow-up appointments. I saw my primary, who was shocked to learn I had been in the hospital but was overwhelmingly positive and encouraging about the next steps. I went back to the cardiothoracic surgeon because I thought my incision was bleeding. (It wasn’t; just draining.) They, too, were supportive and encouraging, telling me to come back if I needed anything. My insurance company assigned me a nurse advocate, and we had a pleasant conversation on the phone. There are services available to me should I want or need them.

Like in most systems, I know it is not the people doing the actual work in healthcare that are the problem. I had mostly positive experiences with my care and felt really lucky to have access to such quality interventions.

But with some of my free time, I’ll be writing to my representatives asking them to please, please, please find a way to make such quality care affordable and available to everyone.

//

I’ve been home for over a week now. I’ve been chipping away at this story a little bit at a time because it’s all I can handle. I’m not sure what it will look like when it’s done or if anyone will even read it. Maybe these are words just for me. Today was my first day home alone since the ordeal, and I think my body appreciated the chance to rest and heal in quiet.

I’m physically cleared to drive but mentally I’m not ready. I took a test drive with Phil on Memorial Day and I didn’t like how I felt afterwards so I called in reinforcements for our daytime driving needs this week.

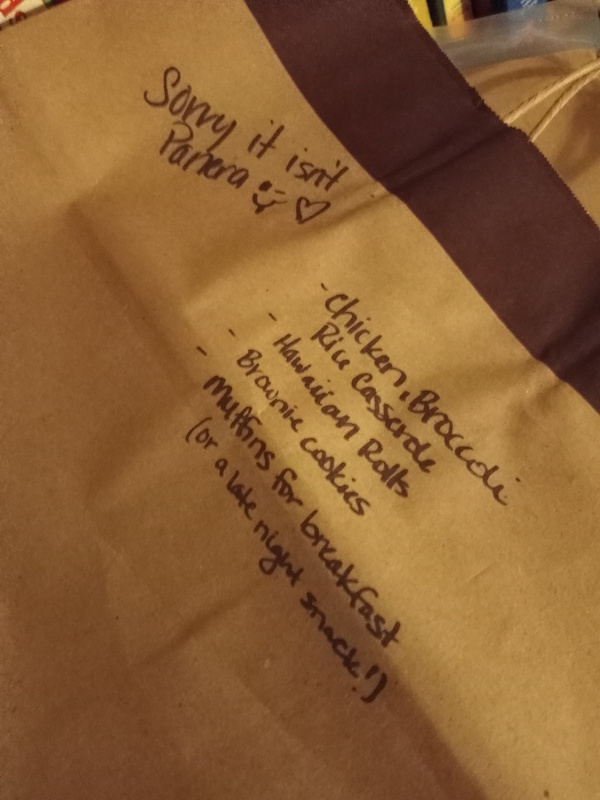

Where would we be without the help from our communities? People have been feeding us for weeks, hardly batting an eye at our needs. Others have donated money to help make up for my lost time at work, for the hospital bills that are yet to arrive. We’ve had so many offers of transportation that it was hard to choose who to ask first. Two different sets of friends took our son to hang out with their kids so he could have some normalcy.

I always struggle with how something like this affects those I love. I feel like a burden, like I’m not doing my fair share, but I’m learning that love never really balances out. We’re always giving and taking and supporting and leaning on each other in so many ways. Yeah, we’re all going to have some shit to deal with when the storm passes, but that’s pretty much a given for life anyway.

I won’t feel guilty because this time it was my turn to need help.

//

June is full of follow-up appointments for me. Then we’re going on a vacation we had started planning before all this went down. I’ll be on blood thinners for six months. Beyond that, I’m hoping for clear scans, positive appointments and continual progress. But as I’ve had to remind myself in the past few days, progress isn’t necessarily going to be as dramatic as it has been. It’s not going to be ICU-to-regular floor kind of change. It’s subtle. A little bit stronger every day. A little bit more stamina every day.

And I have to be okay with that, just as I have to be okay with anything that feels like a setback. There’s a chance my scans could come back showing more clots or that my heart is still working too hard. There may be other health issues that pop up as a result of this.

I confess that I used to think if I had to take a bunch of pills to stay alive that I was somehow in the wrong. I didn’t want that for my life. Now, though, I will do whatever it takes to stay alive, to still be here for my one wild and precious life, as poet Mary Oliver says.

Will I drastically change how I live having come so close to death? I don’t know yet. I know there are things I still want to do, places I still want to go, change I want to see happen. Maybe it won’t look drastic from the outside–no skydiving or bungee jumping; I’m not much a risk taker–but I know I need to shift my focus to what’s important for me.

Stay tuned for how that turns out. I can’t want to find out for myself.